Breathing is one of the most vital functions of the human body. Estimated is that a human being breathes an average of 20.000 times per day. Each breath can have a positive or negative impact on our body depending on how it is performed; and it has been scientifically established many times that healthy breathing goes through the nose.

With healthy breathing, the abdomen gently expands and contracts with each inhalation and exhalation. There is no exertion, the breath is still, regular but above all; through the nose.

However, it is estimated that 30 to 50% of modern adults breathe through the mouth, mainly during the night.

One of the main benefits of nasal breathing is the production of nitric oxide.

Nitric oxide inhaled through nasal breathing has been shown to increase oxygen exchange efficiency and increase oxygen in the blood by 18% while improving the lungs' ability to absorb oxygen. Mouth breathers have a lower concentration of oxygen in their blood than people with optimal nasal breathing; low blood oxygen levels are associated with high blood pressure and heart failure.

Nitric oxide occurs in human breath, but little is known about its origin or enzyme source. Most nitric oxide in the human body (about 25%) is produced by nasal breathing. This molecule is produced in mammalian cells by specific enzymes and plays a vital role in many biological processes, including the regulation of the blood flow, platelet function, immune defense, homeostasis and neurotransmission.

In addition, nitric oxide has many other benefits:

Sleep

Nose breathing during sleep activates the parasympathetic nervous system and results in deeper sleep.

Oral health

Breathing through your mouth has adverse effects on oral health. Increasing the chance of cavities and other oral health issues.

Beauty

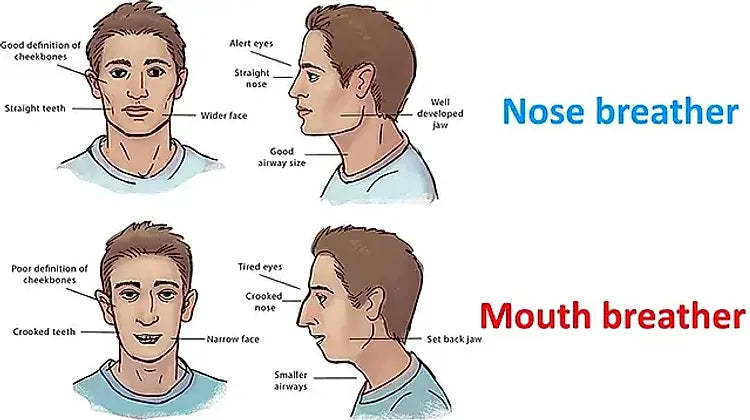

Mouth breathing has adverse effects on facial structure and body posture.

Performance

Nasal breathing has a positive impact on your cognitive and physical performance

Recent research, stimulated by the growing awareness of sleep apnea, has shown that nasal breathing plays an important role in the regulation of breathing in sleep. These sightings are not new; they confirm age-old clinical findings about the importance of nasal breathing in sleep. The earliest description of the harmful effects of mouth breathing in sleep was made by Lemnious Levinus towards the end of the sixteenth century. Two hundred years later, writer George Catlin devoted an entire book to the superiority of nasal breathing over mouth breathing in sleep; and in the late 1800s, Cline, Wells, Griffin, and others showed that obstructed nasal breathing causes sleep disturbances.

Many sleep disorders, such as waking up frequently or having difficulty falling asleep, are caused by an oxygen deficiency due to mouth breathing.

The nose is equipped with a complex filtering mechanism that purifies the inhaled air before it enters the lungs. Breathing through the nose during inhalation and exhalation helps maintain lung volumes and increases oxygen uptake by 10 to 20%.

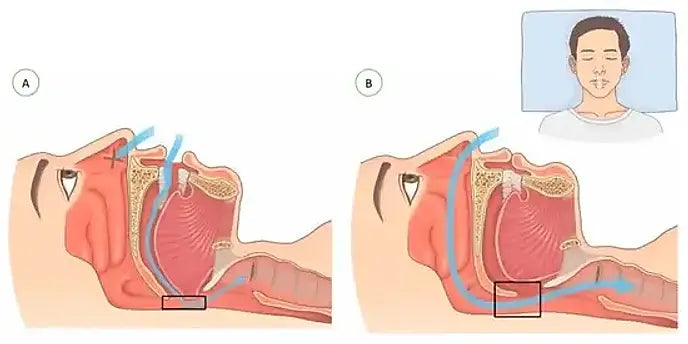

Upper airway resistance during sleep and propensity for obstructive sleep apnea are significantly lower with nasal breathing than with mouth breathing. In the image above you can see the differences between the breathing route of mouth breathing (A) and nose breathing (B).

Taping the mouth shut also significantly reduces snoring. Recent scientific research has shown that about half of people no longer snore after taping their mouth shut. It was found that the worse someone snored, the more significant the improvements were.

Nasal breathing is one of the most important factors for the proper development and functioning of the oral cavity. The air passing through the nasal cavity is warmed and humidified while removing dust and other particles. Obstruction or blockage of the upper airways can negatively influence the most optimal (nasal) breathing. The transition from nose to mouth breathing can have adverse clinical consequences for oral health.

Mouth breathers more often suffer from an overbite and craniofacial bone abnormalities (an abnormality of the skull, jaw or facial structure).

In addition to an overbite, chronically inflamed gums, fungal infections and halitosis (bad breath) are common in mouth breathers.

Mouth breathers are also more likely to suffer from a dry mouth. Dry mouth is not only uncomfortable, it is harmful to the oral microbiome and can negatively impact oral and dental health.Dry mouth promotes cavities because the teeth are not bathed in saliva, which contains certain nutrients essential to the remineralization process.

Dry mouth also lowers the pH of the mouth into the acidic zone, which allows bacteria to thrive and therefore more likely to cause cavities.

Most health professionals are unaware of the negative impact of upper airway obstruction (mouth breathing) on normal facial growth and physiological health. Children who go untreated for mouth breathing can develop a long, narrow face, narrow mouth, high palate, overbite, "gummy smile" (excessive visible gums when smiling), and many other unattractive facial features. (Young) adults can also be confronted with this.

In addition to abnormal facial features, postural problems can also occur in people who frequently breathe through their mouths. Mouth breathers tend to assume a characteristic posture, carrying their heads forward to compensate for the restriction of their airways and allow breathing. This can lead to neck and back pain.

Former Tour de France winner Joop Zoetemelk once said: "You win the Tour in bed". He was one of the first top athletes to emphasize the importance of a good night's sleep. Many subsequent studies have endorsed the impact of a good night's sleep on cognitive and physical performance. The difference between breathing through the mouth and breathing through the nose and the impact of this on (sports) performance has also been extensively researched.

Nasal breathing produces more nitric oxide and this has a positive effect on endurance and strength and promotes recovery. In addition, it has been shown how respiration biomechanics and exercise capacity were negatively affected by mouth breathing; and that the presence of moderate forward head posture acted as a compensatory mechanism to improve respiratory muscle function. This forward head posture often leads to muscle fatigue, neck pain, compression of the intervertebral discs, premature arthritis, tension headaches and dental malformation problems.

Sources